I’m home for the weekend this week and I ran into Manolo.

Manolo is not a family member or a pet… he is the robot vacuum cleaner my parents bought about a year ago in order to alleviate some tension in the home around cleaning.

Manolo is programmed to operate for about 2 hours a day and he goes about the house autonomously sweeping up dust and other debris. He does seem to have alleviated some tension and one big aspect of cleaning has been taken off of my parents’ plate.

Now Manolo and robot vacuum cleaners (“robovacs”), in general, are not enormous works of technology. They’ve been around for years (the first model came into the market in 1996), but have become much more intelligent and autonomous since then and have become a lot more present in homes due to dropping prices (though they are still relatively pricey with models ranging from about between 150 € for the most basic to around 500 € for the most high-tech ($170-$570)).

Models available now generally use sensors to avoid crashing into walls or falling down stairs and Manolo is generally pretty independent except when he gets stuck under furniture and someone has to come to get him. He’s pretty quiet and does his job adequately enough so that sweeping floors and manual vacuuming is no longer necessary at home, though obviously, he cannot get to all areas (stairs and under very low furniture, for example).

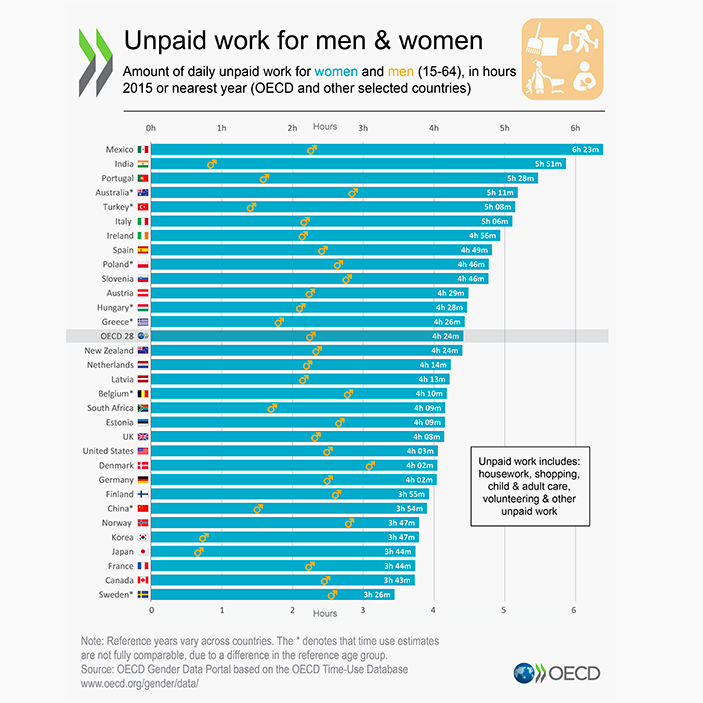

It may seem like vacuum cleaners have nothing to do with gender and gender roles, but the disproportionate amount of time spent by women as compared to men on unpaid domestic labor are still staggering today, even in wealthy Western countries.

You may be surprised to find out that women on average spend about twice as many hours per day than men on household work which includes cleaning and caring for other people (generally children and older people), among other unpaid activities (cooking, errands, grocery shopping, etc.).

The OECD has a gender portal where statistics for all member states (since the making of this table, 8 more countries have joined the OECD) and other non-member countries such as China and India can be compared. Updated statistics can be found here.

According to the 2015 information, on average women in member countries spend 4 hours and 24 minutes per day on unpaid work, whereas men spend half that time (2 hours and 15 minutes). This not only has an impact on perceptions of gender roles whereby women are those that should bear the brunt of the housework, but it also means women have less time to work, study, spend leisure time (or even sleep!) and, thus, are more economically vulnerable. It also attests to the rise of the double burden felt by women which has been linked to increased anxiety and stress levels in women.

The OECD is an organization made up by generally wealthy nations. These are nations where women have already reached the workforce. Women work a full day on the labor market and come home to work another several hours at home. Though women have increased their paid work time, they have not achieved a corresponding reduction in their unpaid work hours. Nor have men increased their share of unpaid work at the same rate that women have increased their share of paid work. This data is further backed up by the 2015 Human Development Report published by the United Nations Development Program.

According to this report:

“Of the 59 percent of work that is paid, mostly outside the home, men’s share is nearly twice that of women—38 percent versus 21 percent. The picture is reversed for unpaid work, mostly within the home and encompassing a range of care responsibilities: of the 41 percent of work that is unpaid, women perform three times more than men—31 percent versus 10 percent. Hence the imbalance—men dominate the world of paid work, women that of unpaid work. Unpaid work in the home is indispensable to the functioning of society and human well-being: yet when it falls primarily to women, it limits their choices and opportunities for other activities that could be more fulfilling to them.”

Autonomous technology, such as robotic vacuum cleaners, can alleviate those burdens placed on women by reducing the number of tasks needed to be carried out by humans and is, thus, a positive influence on general work-life balance. However, its impact is limited. It cannot address the sexist biases and perceptions that underpin this data and perpetuate these tendencies: there will always be housework and caregiving work to be done by humans and if these perceptions subsist, they will more-heavily fall on women.

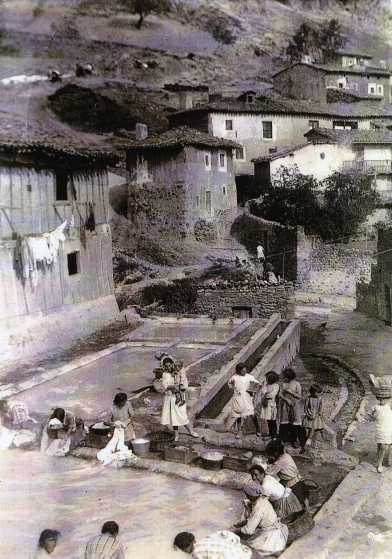

The advent of robotic housecleaning devices (robot vacuum cleaners, self-cleaning litter boxes, air purifiers, robot mops, robot window cleaners) reminds me of when the washing machine became a household item. Before then, housewives hand-washed linens and clothes. In my village in the region of Burgos, Spain, women used to have to go to the public fountain and washing areas in order to fetch water and wash clothes.

Washing machines, which became widely used in the US after WWII but took a little longer to come to Spain, turned an arduous task into something simple, quick and easy. Ads for washing machines around that time generally targeted women.

Washing machines and other home appliances that became prevalent during the second half of the 20th century in developed countries allowed women to start gradually detaching themselves from the home and pursue other more-fulfilling activities, but it did not change the fact that the burden of operating those machines still falls mostly on women and in many less-developed countries where these machines are still not accessible, women are still primarily charged with caregiving and housework.

Autonomous technology as applied to house-cleaning devices will allow many tasks to be completely forgotten by humans, but it will not change tendencies and perceptions regarding gender roles and housework for those tasks that still continue to exist, which means an educational and societal effort still has to take place by which gender roles are actively combated.

Technology is not the panacea, but it is a good starting point to get rid of menial tasks that no-one likes to do and it can also serve to raise some questions to get people thinking about the gender bias that still exists in our day-to-day life. This is the starting point for both men and women to question the reasons behind every-day activities and work towards better distribution of unpaid work.

You can start asking yourselves about what kind of patterns you experienced in your own home with your parents. Were housework and caregiving responsibilities equally spread between both parents? If you live with your own partner, how do you distribute these responsibilities? Is the distribution fair? What are the reasons behind hiring other people (which are generally still women) to clean your house or care for your children? What are the reasons behind investing in expensive technological devices? As a woman, do you feel pressure (internal and/or external) to take on more responsibilities around the house? If not, why? If yes, why? As a man, are you sensitive to these kinds of tendencies? Are you assertive about fair distribution of housework?

If you would like to share your own experience or thoughts about these issues leave a comment or write me an email!